My great grandfather Schlomo Wechsler left Teplik in 1913, headed for Rotterdam and then on to New York. My grandfather Abram Wechsler was recruited during WW1 into the Russian Tsarist Army in 1915. He never returned in Teplik after the war, moved in Minsk and later, to Smolensk. His brother Leo Wechsler died in a fire in Teplik in 1918. Abram’s sister Sarah emigrated to Argentina and by 1918, was living in Buenos-Aires. His other sister Tsilya married a Red Army officer in 1920 and left as well.

My friend Michael Grossmann, whose grandfather survived Auschwitz and whose father took refuge in Switzerland during WW2, has an interest in life stories from this tragic period of history, and suggested that we go to see the place. Being a frequent traveler to Kiev for work, he was able to help with the logistics of the project.

I arrived at the Kiev airport on March 28th at 1 PM but I was not able to leave the airport until 5:30. I heard before I left Moscow that all Russian citizens would have an interview before they are allowed to cross the border. I was asked to leave the passport check area and wait to be invited to an interview. There were fifteen or so men who looked like they were from North Africa, a couple of Russian ladies straight from Egypt (tanned, in sport clothes), and a lady from a flight Riga. There are no direct flights Moscow – Kiev any more.

There were also two Orthodox Jewish men waiting but not for long. I waited for a long time until they invited me to speak. I tried to explain to two uniformed female officers who seemed sympathetic that I will only be in the Ukraine for a very short time, have a mission to accomplish, and every hour is precious. A senior lady officer with heavy eyelids covered with golden eye shadow powder came and explained quietly, after I repeated my concerns, that I just have to wait in the line, because this is what I have to do. A man who looked like he was from Azerbaijan and who had been waiting since 8 pm (7 hours), was finally told he was not allowed to enter the country. This man sat down to make calls, speaking a language I did not understand. What I did understood was that his wife was allowed to cross the border and was waiting for him in vain in the airport building all that time.

After a couple of hours, they invited me for my interview. A young official listened attentively to my whole sentimental story about Teplik. Only afterwards did I learn that the job of the officers was to ask questions and to prepare a video for another official who would decide. I showed to my interviewer a copy of Shlomo Wechsler’s Ellis Island records, Auntie Tsylia’s passport, a print-out of email from Olena Koropova-Zemlianaya, my school friend living in the Ukraine, a paper stating that I work for Citibank. Then I waited and waited. Our waiting companion from Riga flight shared some Latvian bread. She used quite strong words to describe the situation, saying we were being held like “cattle” and treated with disrespect. I thought she was overreacting. An hour later, an official called me in for a second interview. This time it was a young man who started by asking why I was coming from London, asked to prove that my daughter lived and worked in London (Tonya promptly messaged photos of her work permit). He asked what exactly I wanted to see in that place I was going to visit, how long ago I saw the Ukrainian friend who wrote the supportive email, why I gave the guards my friend Michael’s phone number and not my Ukrainian friend Olena’s phone number and why do I call her a friend if I have not seen her since our school days. I mentioned that Olena and I were quite close when we were kids, and bright childhood memories made it easy for us to talk on Facebook. When Maidan events were taking place Olena was fiercly criticizing all Russians (me included). Then the official asked “How did you convince her that you are not anti-Ukranian?”. We ended up looking at my Facebook posts from March 2014 when the first anti-war meetings took place in Moscow and I wrote in English to my Western friends that we were not 3000 people like Russian TV said but 33 times 3000. The young man took pictures of all these posts and asked me to wait again.

Meanwhile, new people joined the line – a business lady nervous to miss her big meeting in Kiev, with colleagues from several countries including Russia and Kazakhstan, and two others looking like mother and daughter. At some point the daughter started to play a loud music on her phone and jumped to dance, energetic turn-arounds and leg-split on the floor. My interviewer, holding my passport in his hand, came and asked her to stop. Then the girl and the officer started a “rap battle”. Then I softly suggested to the officer that he allow the girl to dance a little bit. I also suggested to the girl to not keep him busy with arguing, because he is busy with my case (“look at the passport in his hand, it is mine, and I am waiting till he takes his decision”). The officer came back after a while saying that my Ukrainian contacts did not sound too supportive on the phone. All I could say was I was not able to control who said what, but they probably did not expect the calls. Finally, I was allowed to cross the border.

On the way to the center of Kiev, my taxi driver told me that although the waiting was probably very unpleasant, this is one way to protect the country before the upcoming elections. “Who knows what sort of provocateurs can create problems”, said the driver, “our Ukraine will not survive another Maidan”.

When I finally arrived at the hotel, my friend and former colleague Michael was already there waiting for me, having made it from his Kiev apartment while my taxi was struggling with traffic jams. We went to dinner, 2 metro stops from the hotel (“University” – “Khreschatik”).

The first restaurant was exploiting the Maidan revolution theme, and was named “The Last Barricade”. At the restaurant entrance, they ask you for a password. We could not begin to guess, so the three foot tall Guard told us the password and we repeated – “Fight, and you will win” (“boritesa – poborete”).

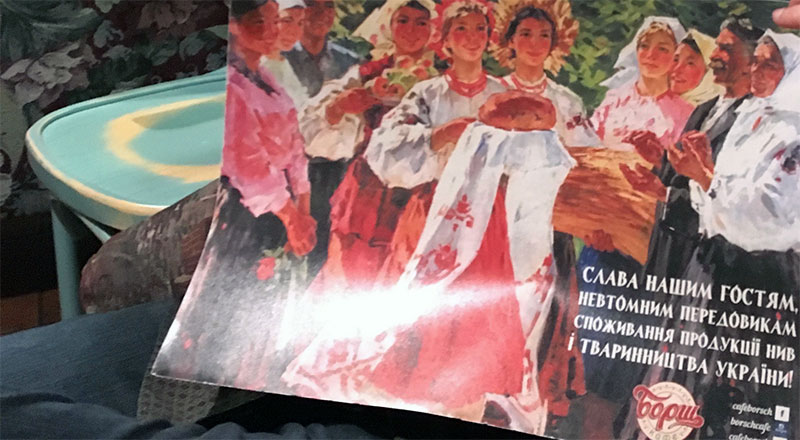

Another restaurant was named “Borsch” after the traditional Ukrainian soup made of cabbage, beetroot and tomato. The place looked unpretentious, but the food was good. The place mats on the table played with 1950s imagery – portraying stereotypical Soviets workers, prosperous and proud of their harvest.

Next day, we headed to a big bus station near the central railway station and found a mini bus ready to go to Uman, a key destination point on the way to Teplik. We waited one and a half hour for the minivan to depart. Michael could not believe all the waiting and went somewhere to ask about the delay, and got an explanation: “On Fridays, buses from Kiev leave not according to a schedule but when they are full, but on the way back one can count on a scheduled departure”.

A nice young girl sitting behind us promptly advised that we’d better order our evening bus back as soon as possible. We took a phone number from her to make a reservation.

On the bus, the radio played pop songs, mainly Russian. Most passengers were sleeping, only a man sitting behind us squeezed between the nice girl and a very big lady with a crutch (the red-faced driver on the bus would not leave without this last tiny spot occupied), interviewed Michael about his views on candidates for upcoming Ukrainian presidential elections, and asked about life in France. At some point he shared a secret, which probably only guards working at Ukrainian dairy factories, like he does, know, “Good cheese made from Ukrainian cows’ milk is exported to France to mature until it is moldy and blue, then it gets sold back to Ukraine, because your French cows are not like our cows, you know”.

Approaching Uman after three hours we were told that there was a must-see remarkable park in Uman, “Sofiiskaya”, built by Prince Pototskii for his wife. (we did not make it to this park, did not have the time).

While at the bus station in Uman, we talked to a taxi driver standing near an old Volga. He very quickly agreed to bring us to Teplik and back for 1200 grivnas, then Michael mentioned that we might need some driving around Teplik as well . We finally agreed on 1500 grivnas. We got into the car. At first, I thought the engine did not sound good but it proved to be working alright.

Some parts of the road to Teplik were quite bad. However, the land along the road looked cultivated. We noticed the occasional pre-election poster along the way with portraits of Poroshenko, the slogan was “there are many candidates but there is only one president”.

After an hour and a half we have arrived at Teplik:

A little way down the road there was a big memorial sign. Michael went to take photos and then googled the name. The composer, Mikhola Leontovich, tragically died in the early 1920s. He wrote beautiful contrapuntal choral pieces. The words on the memorial stone read “the Ukrainian Bach”.

Arriving in the little town of Teplik, we saw the sign for a children’s music school and two ladies were standing on its porch. I got out of the car and told them that my relatives lived here more than one hundred years ago, that I did not expect to find anything in particular but just wanted to get the idea of the place… maybe they could tell me where Jewish community used to live, maybe there was a cemetery left? They explained how to drive to an old cemetery – left, right, then there is a lake, and then the cemetery. And, one of them added, it will be good if you could find a man whose name is Leonid Brokh, he is very much into the history of the place, he might have something to tell you.

The cemetery was a sad place. Big empty area with old tomb stones here and there, impossible to read what was written on them in Hebrew one hundred and fifty years ago, or more.

But there were a few tomb stones, which looked like they were tended to, and fairly recently.

But again, all in Hebrew.

At the far end of this field there was what seemed from the distance to be a modern cemetery.

These were late 20th century tombs. I looked at them all and found a familiar name – Voloshin. Auntie Tsylia told me that her and my granddad’s sister’s Sarah married name was Voloshina, and she left to Argentina with her husband. Maybe the person buried here was related to this Voloshin.

We asked some local passers-by where to find Leonid Brokh and they showed us the way. It was not difficult to find the house.

First, we did not know if we could just approach the house and knock, then Leonid’s neighbor helped us, making a phone call to Leo’s wife Liuba.

A street in the district of the town, where I believe Jewish population lived:

Leo told us later that the lake we passed on the way was in old times called “Zhidovskoie”. “Zhid” in Russian is a derogatory word for “Jew”. But in Ukranian, I heard this is just a word referring to the nationality. Which of course does not make it sound any better.

Leo’s house, photo is taken from his neighbor’s yard:

We talked to Liuba first, and then 20 minutes later her husband arrived. “What is your family name? Wechsler? Sounds very familiar. Welcome! Made all the way to Teplik, what big hearts you have”.

I explained that I came just to see the place, with no particular research purposes.

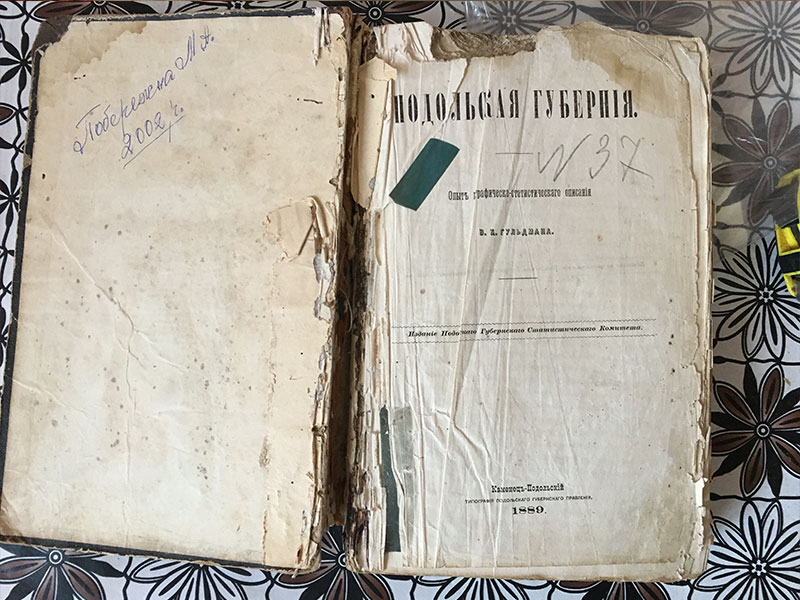

Leonid showed us a book published in 1889 about the Podol district, as it was called when Ukraine was the part of the Russian Empire. While I was talking, Michael took photos of some pages, with main facts and stats about population, industries and gross product. This page here says that at that time 5000 people lived in Teplik, 53% of the population were Jewish. There were 614 households, one Christian church, one synagogue and three Jewish houses for prayer.

Today, there are only 5 Jewish households in Teplik, Leo said. Two thousand Jews were killed by Nazis and policemen they recruited locally. This happened on May 27th 1942. First, all were held at the center of the village near the synagogue, then they were forced to go uphill, leave their clothes at some point on the way. Leo said that there was a tree with a memorial plate there but then someone cut the tree to build a house although he was warned against building on such a spot. There is indeed a big house but, Brokh said, the man got mad, and his wife left him, and his child does not want to know him.

After that place the naked people were forced to go further uphill, about half a mile or so, to the outskirts of the village. The “Road of death”, Leo said. We got out of the car and saw what looked like a graveyard far to the right and several graves on the left, near the road.

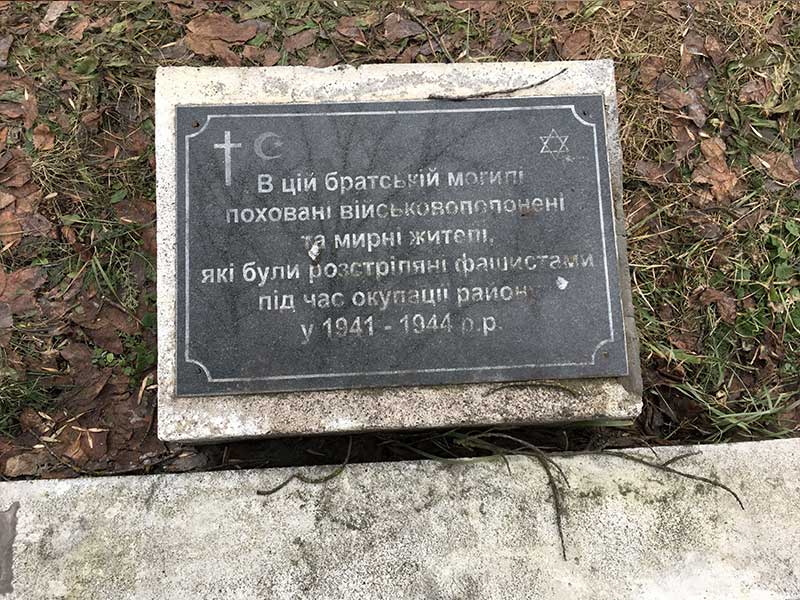

For a long time, there was just a little tomb here, the one seen far behind in the picture above. In the years after the terrible events, the earth started to push out bones, many of them small and thin, those of children, so it was decided to put these low fences around quite a large area, and try to restore as many names of people killed there as possible. I asked why a Muslim sign was on one of the tombs, and Leo explained that after the killing of the Jews, Nazis were still using this place for the same purpose. Two wagons of prisoners of war once came to the village, and among people shot dead here were Kazakh and Kirgiz soldiers and officers.

We understood that people whose relatives were killed here, or people related to Teplik in this or that way, donated to build and maintain this memorial place, and Leo has been leading and organizing this.

When we were back in the car, Leo said to the driver: “we must show people, mustn’t we, that there are no fascists here whatsoever” referring probably to comments that Russian TV spreads – that nationalism is “raising its head” in the Ukraine.

Arriving back to Uman to catch our minibus leaving at 6, we had to have a rather awkward talk with the driver who mumbled about “1500 grivnas, this is just the way there, and look at how many kilometers I made, look at the calculations” showing us a piece of paper with few figures and final balance of 2100 grivnas scribbled on it. Unpleasant as it was, we paid what he asked for. We just could not argue with him after this long and emotional day. Hopefully the money did him good.

Next day, March 2nd, Saturday, we went to Baby Yar – being in Kiev three or four times, I never visited that place before.

In the morning we had coffees in a couple of nice places including this shop of ladies clothes.  Michael bought a shapka, a cap, as it was quite cold with strong wind. The LGBT hat (rainbow) seemed the only unisex choice. The shop is called Subur-B Clothes and is on 10 Proreznaya Street. I bought some colorful gloves and got my 50% discount card for all future visits.

Michael bought a shapka, a cap, as it was quite cold with strong wind. The LGBT hat (rainbow) seemed the only unisex choice. The shop is called Subur-B Clothes and is on 10 Proreznaya Street. I bought some colorful gloves and got my 50% discount card for all future visits.

There were lots of nice dresses in this shop.

We took the metro to go to Baby Yar. The metro station is called “Dorogozhichi”.

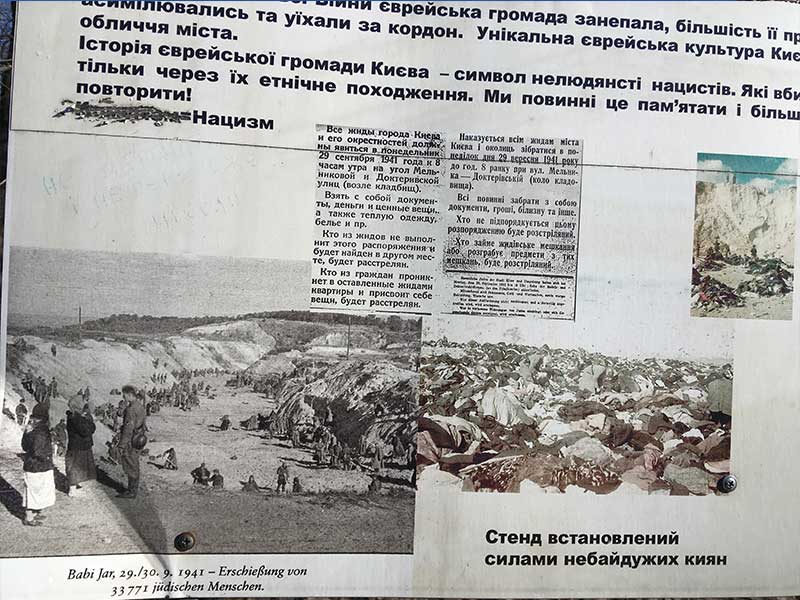

“Yar” means ravine. In 1941, on September 29th-30th, 33,771 Jews were killed here.

During Nazi occupation in 1941-1944, 100 thousand people were killed – civilians, prisoners of war, Jews, Gypsies, patients of clinics for mentally handicapped people, participants of Ukrainian national resistance movement.

To children:

To Gipsies:

On the stands in the park – photos from archives, of the place and of announcements in local newspaper: “All Jews of Kiev must be at 8 in the morning at the corner of Melnikova and Dokhterieva streets, with their documents, valuables, underwear, warm clothes. Those not obeying this order will be shot. Those trying to occupy flats abandoned by Jews – will be shot”.

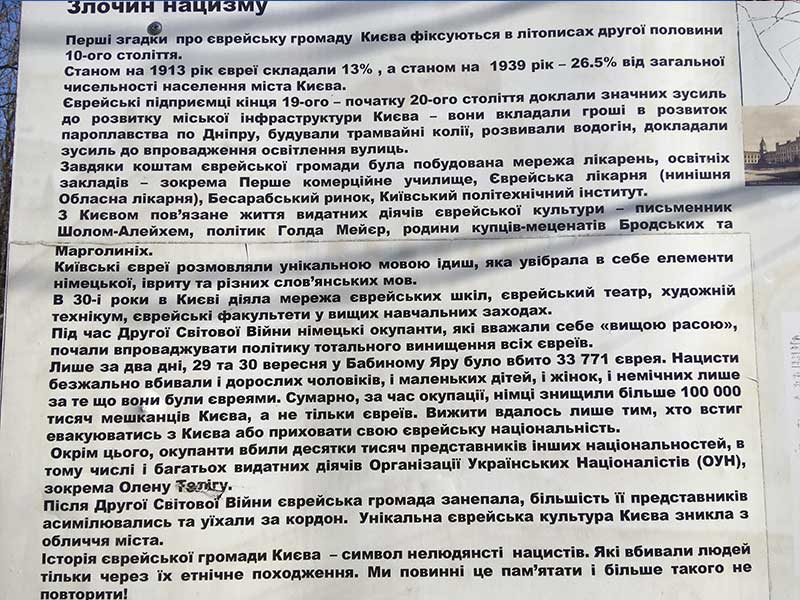

This article below, in Ukrainian, briefly tells the story of the Kiev Jewish community and its contribution into the development of industries and culture.

In local chronicles, Jews are first mentioned in the second half of the 10th century. In 1913 they constituted 13%, in 1939 – 26,5% of Kiev population. After the Second World War the community ceased to exist – the people emigrated to other countries or assimilated.

The title of this poster is “Crimes of Nazis”.

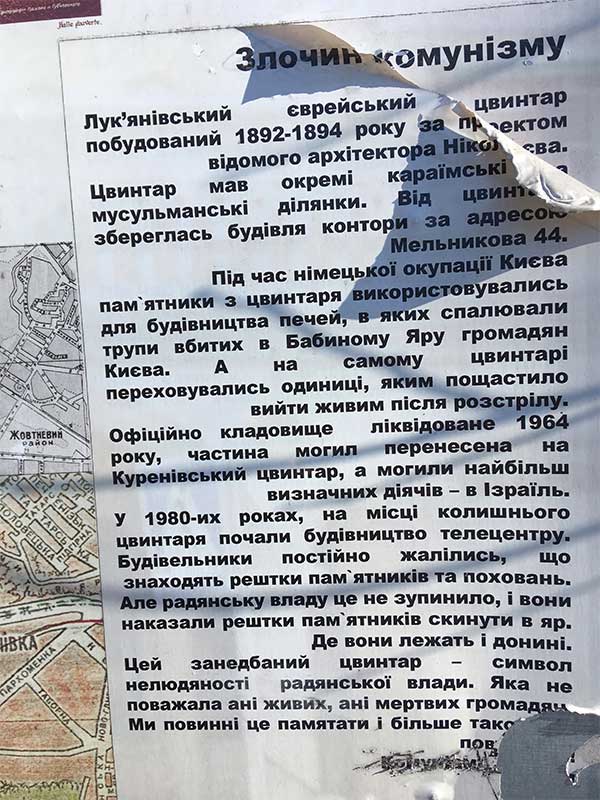

Another one is «Crimes of Communism»:

From this article I learned that Baby Yar was historically a place of the Jewish cemetery founded in 1892-1894. There were Tartar (Keraim) and Muslim parts of the cemerery as well.

Under Nazi occupation, at the time of mass killings the tombs of these cemeteries were destroyed and the stones were used a to build crematoriums to burn dead bodies. In 1964, Soviet authorities officially eliminated this cemetery. Some of the tombs was transferred to another cemetery, Kurenevskoye, some of the tombs of well-known people were moved to Israel. In early 1980, they started to build a TV center here, and builders were complaining that they were finding tombstones and railings in the ground. The tombstones are still there.

Then we came back to the city centre and went to this Jewish cafe called “Zimes” on Sagaidachnogo Street:

Kiev is a very beautiful city:

People are friendly and good-natured. They look happy and relaxed even on those street posters, which remind about the ongoing conflict with Russia in Donbass, former miners’ region in the east of the country.

“Fighting together and playing together”.

Or – “Go defend your country, sign the army contract”.

This panda hugged me on my way to the airport, before we got into taxi. “You must be from Russia. Moscow or Saint-Petersburg? Here is what I have to say: we love Russians because you are kind people, we only do not like your politicians. Please share this with your friends, tell everyone you are welcome here!”

March 4th, on our ways to Paris via Amsterdam and to Moscow via London:

I was sure before the trip that it would go well, and it did.

Merci Michael. Sans toi, je n’aurais jamais tenté ça.