Русский

Electrifying Smolensk villages

Five years since the USSR sent Yuri Gagarin into space, some villages in the the Smolensk region still used candles.

(Surrounded by forests, lakes and mires, some villages were even not occupied at the time of Hitler invasion. Hard to believe that there were spots of “Soviet power” in the region ruled by Nazis from July 1941 through September 1943.)

Students were apparently a precious resource for the Soviet state electrification programs. They did hard physical work, and at the same time delivered highly professional engineering solutions. They were also happy with any payment. The war and the post-war difficulties were a living memory, capitalism with its luxuries was somewhere very far away.

Propaganda was ubiquitous but not omnipotent. As I know from my parents and grandparents, families had their own narratives about the past, and most people were busy surviving and building life for their children.

The builders

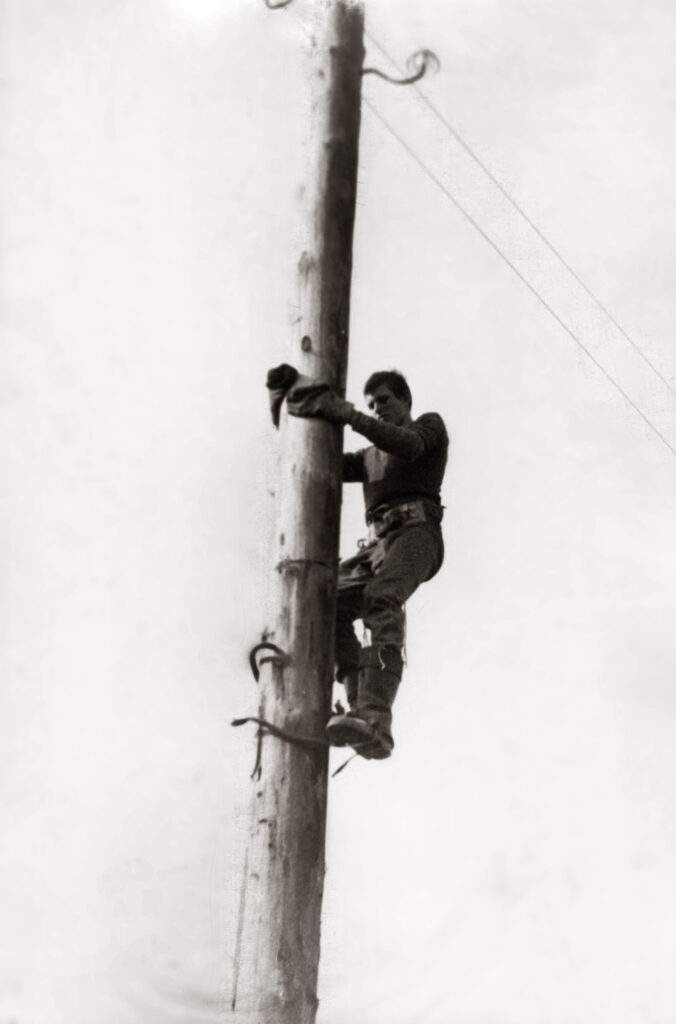

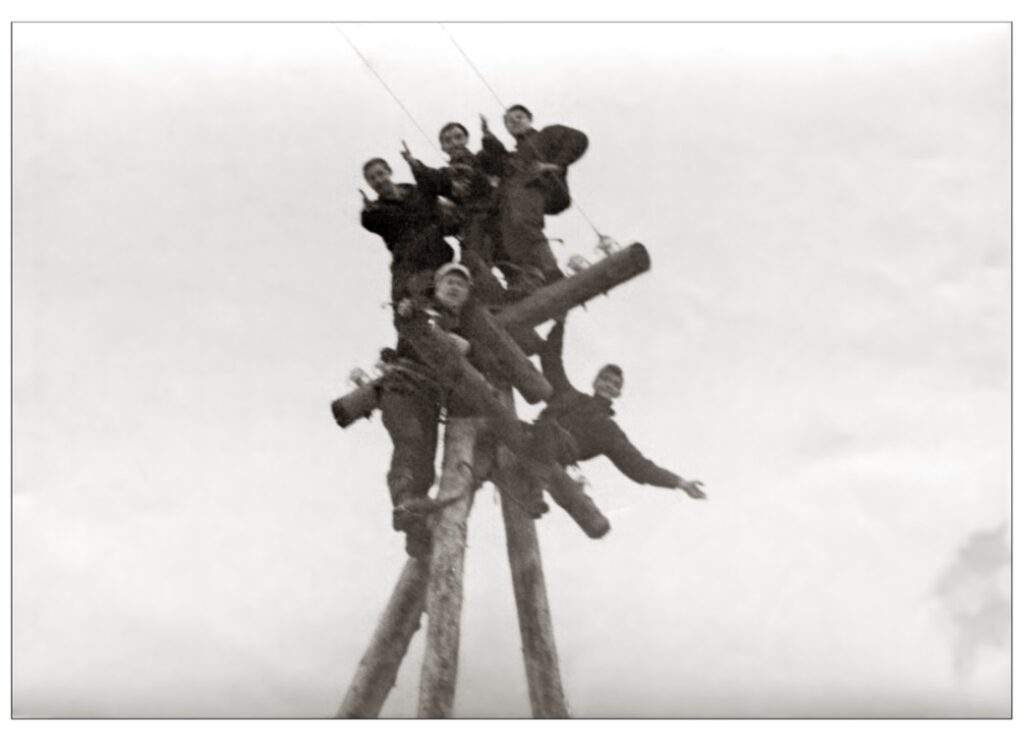

First, the brigade cut the forest to make a 30-metre-wide line, and rolled the electric wire along.

The photo shows a tractor “sleigh” with a reel of wire on it. Tractors’ runners, made of logs, had to be very strong as the tractor pulled forward with no regard for the quality of the road. The end of the wire was fixed at the starting point, the tractor pulled this structure, the wire lay down. Then, dad’s team would put up the poles, the wire was thrown onto the poles.

The poles are called “candles”. They were a lot of work. The place where the concrete part – called “stepchild” – had to be flat, smooth and neat, otherwise the concrete “stepchild” would dangle.

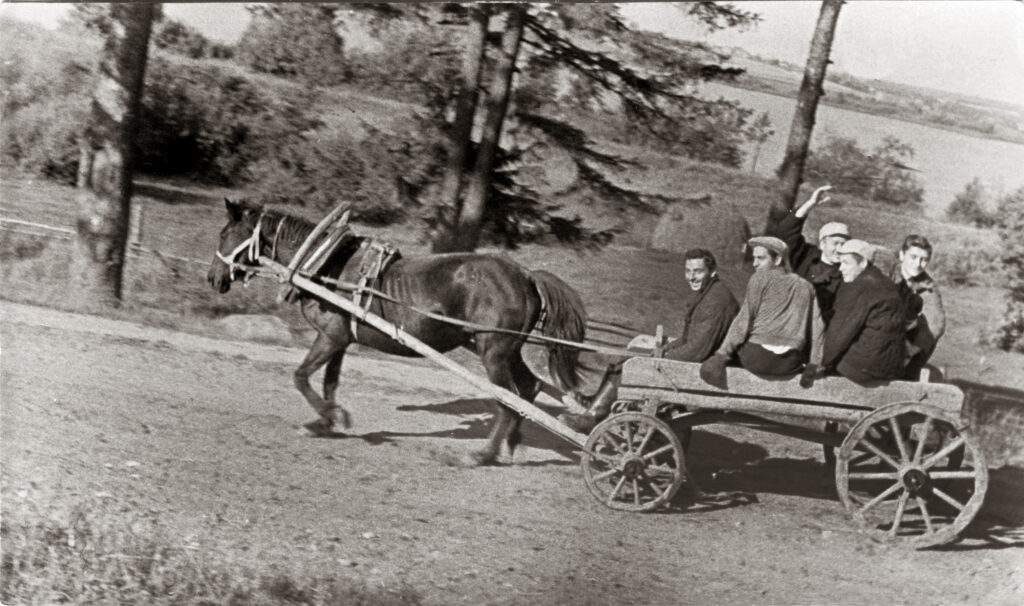

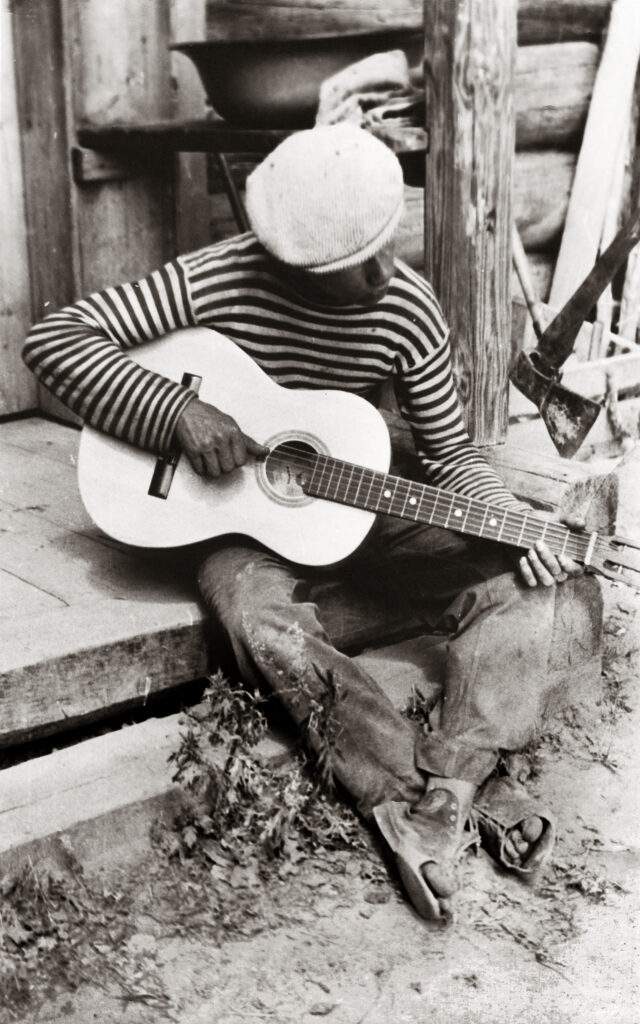

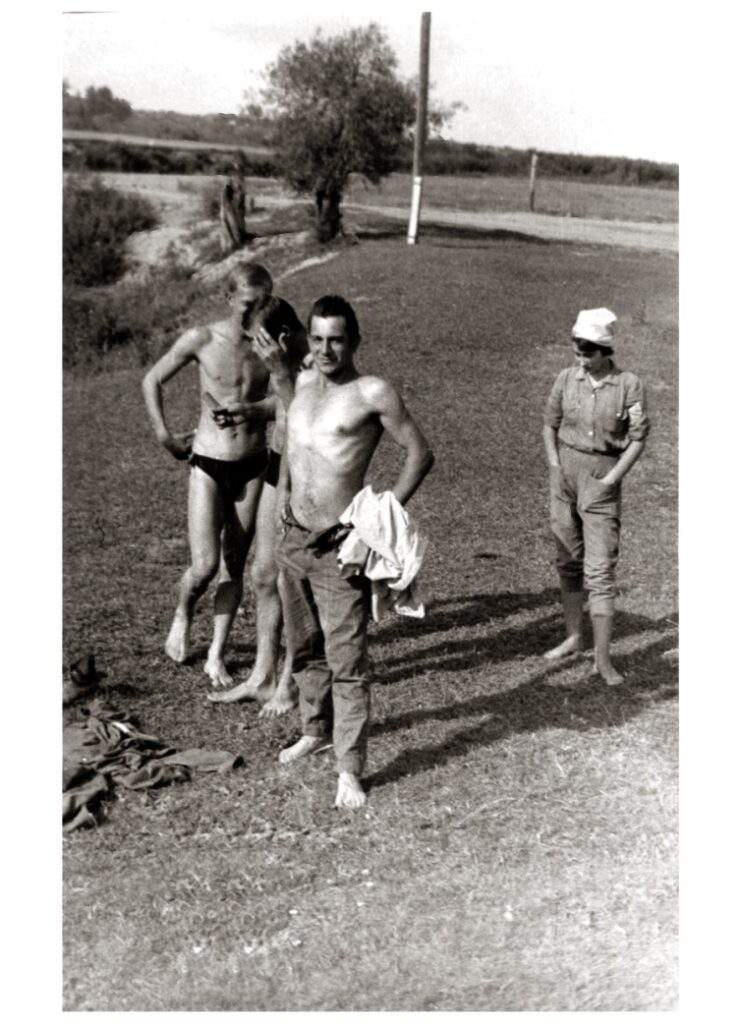

The students

Dad speaks very high of his team, young men from Russia (Moscow, Smolensk), Ukraine and Kazakhstan. They were all students of Moscow Power Engineering Institute and knew all about electric systems. In 1961 MPEI opened a branch in Smolensk. Dad and Mum became students in 1963. Dad dreamed of the Leningrad Institute of Film Engineers, but had to stay with his parents in Smolensk for various reasons. Mum was quite a literature lover but did not even think of studying humanities. Engineering was considered a proper profession, and a good education.

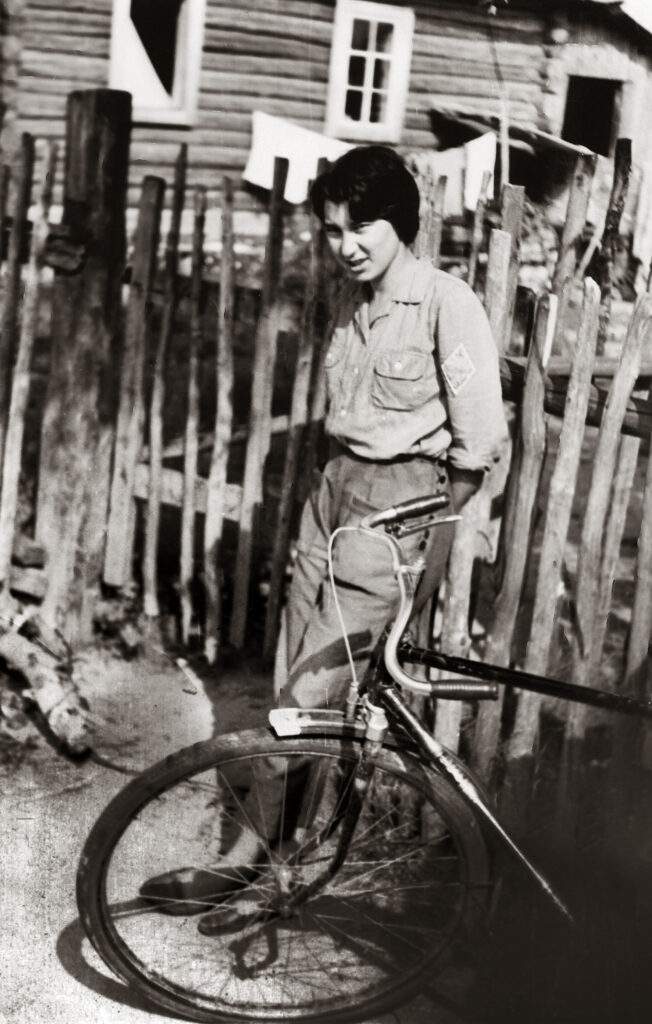

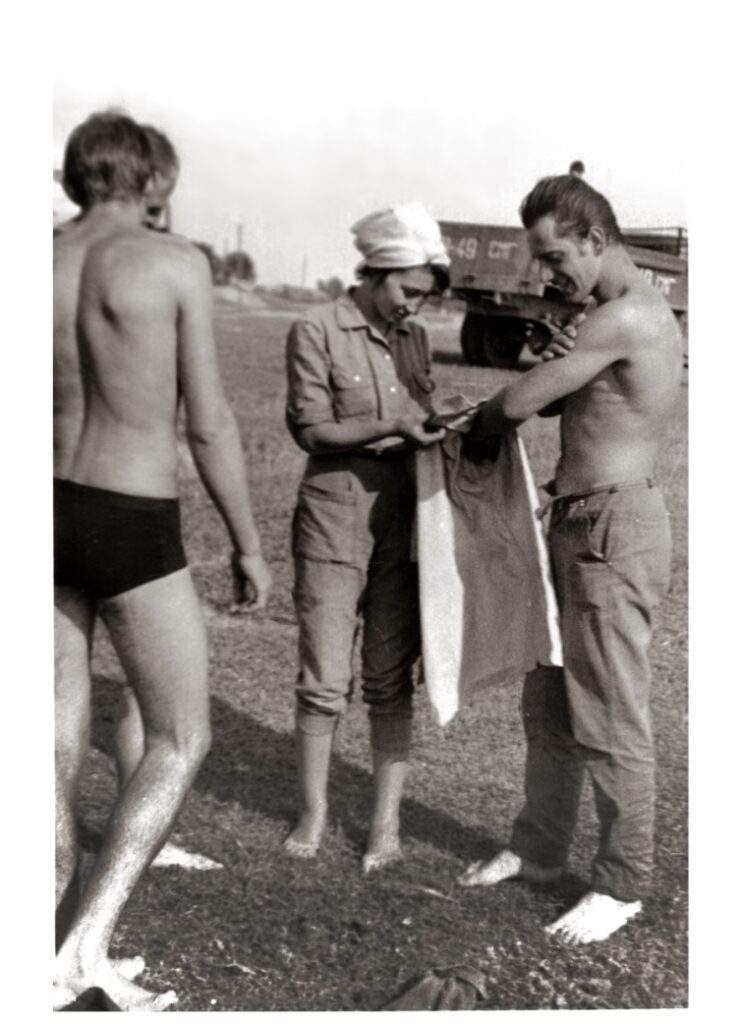

My parents became romantic friends after their first year in the Institute, so mum joined the electrification team, to cook meals for them.

Proud to be engineers

Dad have worked fifty years as the chief technical designer of the Smolensk Radio Components Plant (as of today, 31.03.2024, still there). Mum worked as a designer in aviation industry, then at a plant that produced various calculating devices; she managed groups of designers and engineers, overlooked production process and was highly respected by the workers of the plant. She had to retire early when the computing devices plant was privatised and turned into a parking lot with a canteen. I remember what a stress for her it was, in the early 1990s.

Back to photos

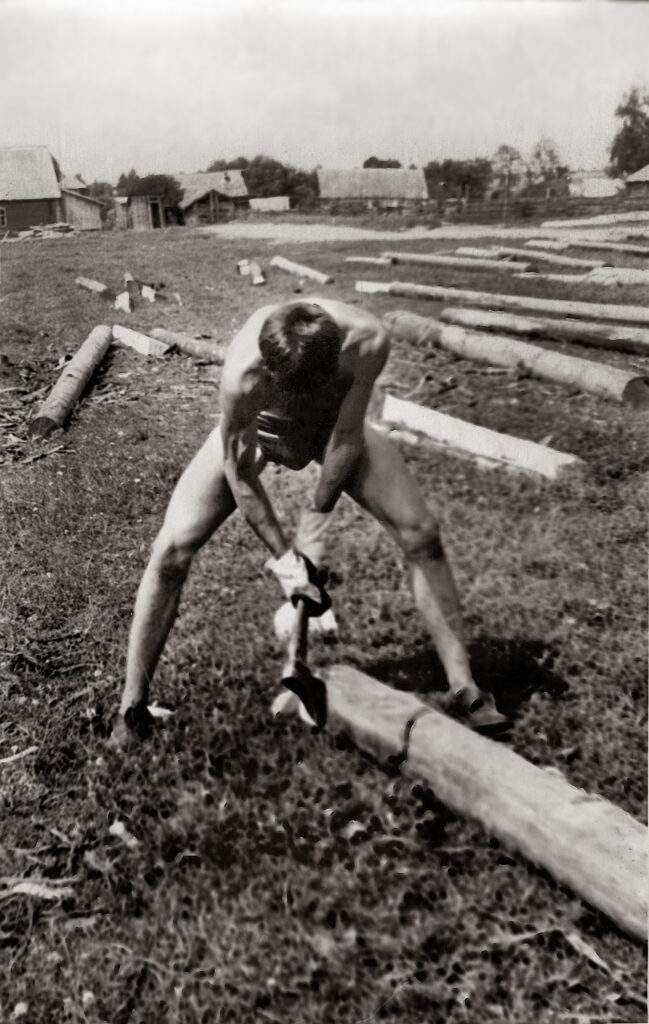

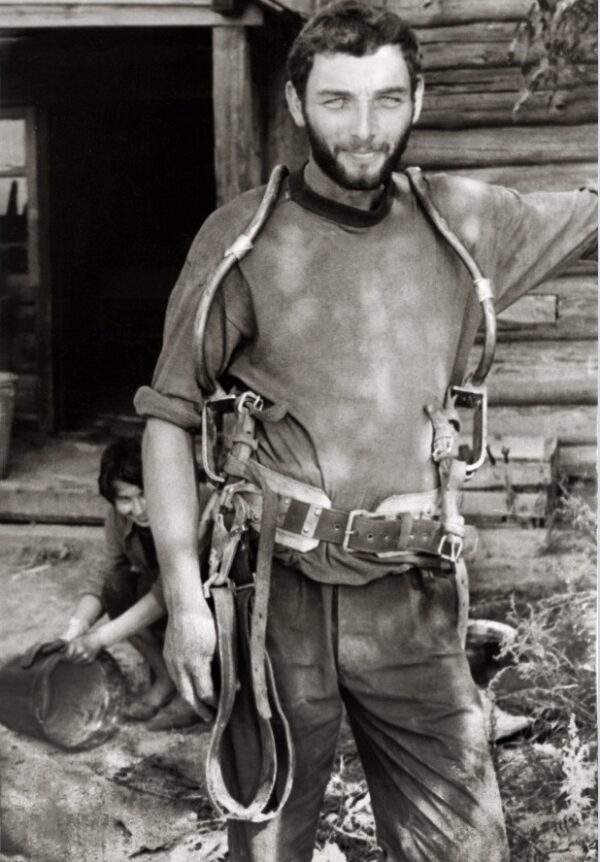

Why is he wearing rags?

My parents laughed when I asked this. They had new glossy uniforms, dad said, but the wooden parts of the poles had been moisturised with chemicals (creosote) that destroyed clothes almost instantly.

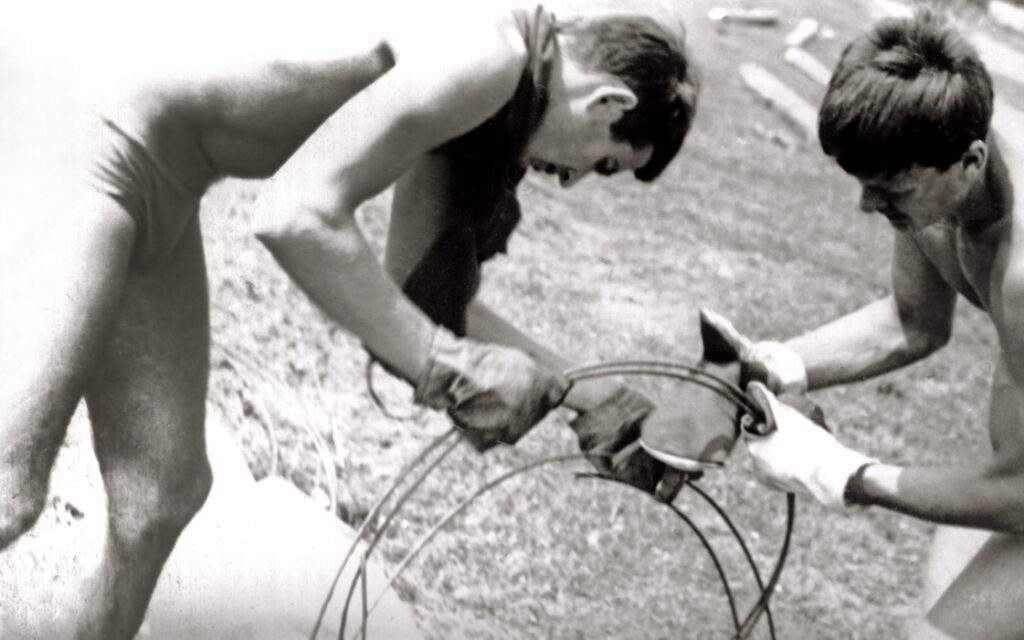

…They built a field kitchen for mum:

Dad was the leader of the team, responsible for the results of the project, and for the people. They worked very hard and came up with their own know-hows for efficiency. They neither drank nor smoked. Healthy, sportive young people, rather detached from Communist ideology, busy studying electricity and electronics in winter, busy working in summer to bring light to rural homes lost in the woods.

Looking at the photos now, I envy these young people. The mid-1960s seemed not a bad time to be twenty in the Soviet Union.