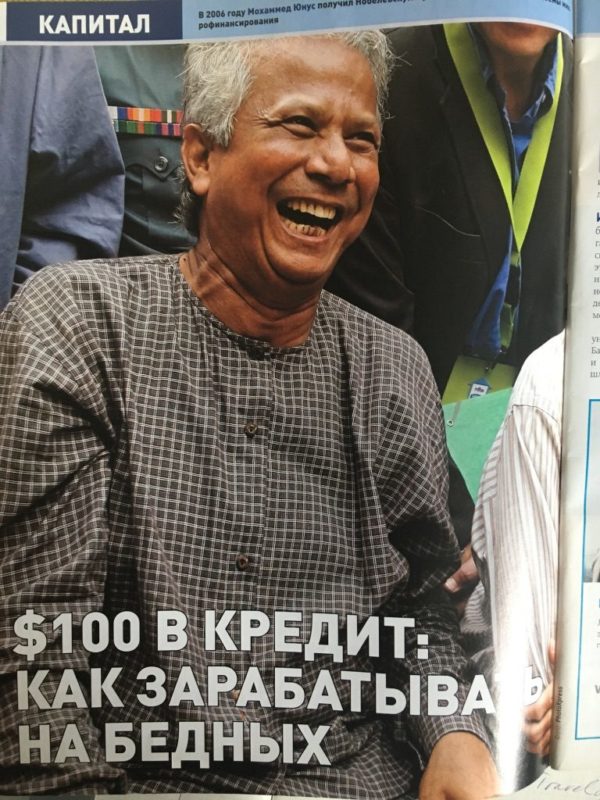

On the photo: “$100 loan. Can one earn anything, lending to the poor?”

In 2008, my daughter, a student journalist at the time, was looking for professional experience and wanted to get published. I proposed a topic, and she wrote an article based on “Banker To The Poor”, a book by Muhammad Yunus. The article appeared in a magazine called “Finance” in March 2008. Here it is, with some information I added from my own experience at the EBRD Small Business Support Fund.

March 2008, «Finance» magazine

Sberbank intends to make use the world-renowned experience of Grameen Bank, Bangladesh. However, there are doubts that the system based upon 100-200 dollar loans will work Russia.

Who would have guessed such a development, when microfinance was first tried? Today, microfinance it is a whole range of financial services for the poorest but economically active groups of population. The most famous of these services is microcredit, although there are also different types of deposits, insurance, etc.

History

The first specialised microfinance bank was the Bangladesh Grameen Bank (“grameen” means “rural” in Bengali). It was founded in 1983 by Muhammad Yunus, university professor of economics. Today this man is referred to as “the founder of global microfinance,” but 30 years ago, when Yunus was just starting out, he was treated with scepticism and his initiatives were regarded as charity and having nothing to do with profit making.

In 1974, a young professor, Mohammed Yunus, after completing his PHD in economics and working in Middle Tennessee State University in the US, came back to his native Bangladesh to teach economics. At that time, severe floods inundated rice crops and led to mass starvation in the north of the country. Hundreds of poor, exhausted people from remote areas came to the cities. No measures taken by the government helped: there were too many hungry people. “I was a scholar in love with elegant economic theories, and I wanted to give my students knowledge that could help heal social problems of all kinds. But in 1974, I started to be afraid of my own knowledge. Why would one need all those theories when people were dying on the sidewalk opposite the building where I was lecturing?

The idea

Yunus talked to a poor village woman who was making bamboo chairs. To make them, she bought raw material every week. The money for the purchase (5 taka=0.22 dollars) had to be borrowed from intermediaries, to whom she sold her goods at a price slightly higher than that of bamboo. Thus, the income from hard work was negligible (about 2 cents), and it was enough only to not starve to death. And so it lasted for years. This woman was in a vicious circle of poverty just because she didn’t have 5 takas to buy the raw materials for production! In her problem Mohammed Yunus saw the problem of all the poorest people: they were neither lazy nor stupid, there was simply no financial resource to help them realize their economic potential. In the absence of a credit market for the poorest people, local informal moneylenders became the providers of financial services.’

The easiest way for Yunus to clear his conscience could be a 5 taka donation, but he decided to change the situation radically and began working towards the creation of a bank for the poor. The first loan still came out of his own pocket – $27 for 42 people. Then he applied to the local bank, where he received an official loan of $300. A crucial moment was Yunus’ meeting with a board member of the Bangladesh Agricultural Bank. This man was inspired by Yunus’ idea and made Grameen a branch of his bank, only formally dependent on the head office. Then, with the help of the Governor of the Central Bank of Bangladesh, new Grameen branches were established on the basis of other state banks. Step by step, Grameen gained independence. Now 50% of the bank’s co-owners are its borrowers. “I never imagined that my microcredit program would become the basis for a national “bank for the poor” serving 2.5 million people, and that it would be adapted by more than a hundred countries on five continents. I was just trying to deal with my feeling of guilt and satisfy my desire to do something good for others. It all started with a few people, they took a loan, the loan helped them survive.” In 2006, Muhammad Yunus won the Nobel Peace Prize for the microfinance system.

Forget collateral!

Yunus questioned the underlying bank credit principle – the collateral of the loan. And it worked! 98% of the first batch of loans issued by the bank paid back. It was the principle of group lending that became an alternative to collateral.

Loans were issued provided that borrowers form groups of five, where each participant is responsible for the other. In addition, payment discipline is ensured by repayment schedule: repayment starts a week after the loan is issued, even weekly payments include both interest and principal amount. The rate for a one-year repayment period is 20%. It should not be lower than the market rate, otherwise those who can get a traditional bank loan will try to present themselves as the poor needing a micro loan. It is very important to clearly define the target group and keep the commitment to the target group. In the case of the Grameen Bank, this is the poorest working population; for such people, credit was the only chance to break out of poverty. But if poor and wealthier people mix, the benefits might not go to people for whom they are meant.

Microcredit operations similar to the Grameen Bank programme are now <written in 2008> operating in 28 countries, including developed countries (Germany, USA, Poland and France). The principles can be applied in any communities that are in need of quick small loans to micro enterprises.

Russia in the 1990s

The idea of microcredit inspired certain developments in the banking industry in Russia in the 1990s. Nothing like repeating Grameen though, because Grameen emerged in a small settlement with little infrastructure and impoverished population. However, In Russia, small towns – “satellites” of large state plants – were in similar situation. People were not paid and they left their state jobs, and a typical picture was that half of the city’s population became “shuttles”, and the other half became their clients. Former teachers, doctors and engineers started to travel to buy goods from other cities and neighbouring countries, only to re-sell the goods in the street. Typically, electric supplies were bought in Russia and brought to Poland, and clothes would be brought back, to sell in Russia. This trading for many people meant survival, and some people managed to build wealth. Many “shuttles” – in the Urals, Siberia, Tula and Nizhny Novgorod regions – received loans from Russian banks (based on funds provided by the EBRD), through the EBRD Russia Small Business Fund, which promoted the microfinance know-how.

Successful street traders would open shops and then expand their business. Many RSBF clients made their first money on “buy and sell” work but then started small production facilities – printing shops, bakeries, water bottling operations, or cafes, restaurants, transportation companies. As part of their cooperation with the EBRD, Russian banks trained hundreds of loan officers to work with SMEs, and the “EBRD method” was formalised on the level of guidelines and procedures. The smallest loan under this programme was issued technology in Pervouralsk, and it was just 500 rubles ($17 at the time of issue). This was the amount a woman entrepreneur needed to make a purchase of cosmetics goods for subsequent distribution.

It is difficult to imagine such a thing today, in Moscow, Saint-Petersburg, Yekaterinburg and other cities of Russia.

However, microfinance continues in developing markets. Important factors of success are the enthusiasm of employees who communicate directly with clients, a tailored approach to client entrepreneurs and the focus on the target group.