First Session. The place, the time, the first two chapters

The action takes place in Moscow, near Patriarch Ponds, in Moscow city centre. The historical name reminds of three ponds and patriarch’s residence located here in the 18th century. Today, the place is associated with expensive property and fashionable cafés. There is one big pond, with trees and benches around it, just like in the novel. The “naughty apartment” at 10, Sadovaya-Triumphalnaya Str. (Sadovaya 302-bis in the novel) hosts Bulgakov’s museum since early 2000s. The Tchaikovskii Concert Hall’s building, Vsevolod Meyerhold’s theatre in 1922-1938, could be the Variety Theatre in the novel, with a round stage and an amphitheater hall. A tiny green park in the yard behind the theatre is still there; Spiridonovka street is real, too. The manor in Tverskoi boulevard described as Writers’ Centre (The Maxim Gorky Literature Institute today) is not far away from the Patriarch Ponds. One can easily follow the route of Ivan who ran from the ponds to Moscow river, and then to writers’ restaurant.

As for the time, May 1937, it was a hell of a time. Still, the lindens near the pond were blooming and people loved, struggled and hoped. The author of the novel makes jokes about disappearing people, sealed doors, polite employees of a certain organisation, the “housing problem” that has deformed Muscovites… All that could be a pure joy to read and laugh at, had we not known, today, about Gulag and purges. How do between-the-lines messages translate into English? In our reading group, the Russians and the British participants read same things differently.

“Master and Margarita” abounds in references to other literary works, and to music. It is indeed a book about books. In today’s terms: the text offers a lot of hyperlinks to click. However, even without deep dives into the 1930s and without appreciating its numerous opera associations the reader will still enjoy the novel, and the soundtrack: “and after her flew the completely insane waltz”, “the famous Griboedov jazz band struck up”, “the orchestra… hacked out some incredible march of an unheard-of brashness”.

In the first chapter, two writers get into a conversation with a tall foreigner carrying a stick with a black knob shaped like a poodle’s head, “right eye black, left – for some reason – green”, unmistakably the Devil. The foreigner, “a professor of magic”, talks about Pontius Pilate and, in passing, predicts death of one of the writers, Mikhail Berlioz. The prophecy come true the same evening.

Why does the well-read propagandist Berlioz get punished, and by whom? The group was bound to discuss the theme of artist’s calling and of Soviet writers’ political engagement.

To take a new breath after the serious discussion, the group looked at the English translations of the foreigner’s (he calls himself Professor Woland) ironic expressions. The participants also read the epigraph from Goethe’s Faust and its broader context, in Russian and English, and “played” several dialogues, such as this one:

‘No, we don’t believe in God,’ Berlioz replied, smiling slightly at the foreign tourist’s fright, ‘but we can speak of it quite freely.’

The foreigner sat back on the bench and asked, even with a slight shriek of curiosity: ‘You are – atheists?!’

‘Yes, we’re atheists,’ Berlioz smilingly replied, and Homeless thought, getting angry: ‘Latched on to us, the foreign goose!’

‘Oh, how lovely!’ the astonishing foreigner cried out and began swivelling his head, looking from one writer to the other.

‘In our country atheism does not surprise anyone,’ Berlioz said with diplomatic politeness. ‘The majority of our population consciously and long ago ceased believing in the fairy tales about God.’

In the last part of the first session we turned to chapter two, the first of the four counterpoint chapters that form “the novel on Pontius Pilate”, a book within the book. The themes of power, authority, violence and “washing one’s hands” emerge. At this point, the message the author conveys by his own interpretation of Jesus and Pontius Pilate story is not fully clear. To prepare to discuss Bulgakov’s attitude to religion at different stages of his life the group had read excerpts from Marietta Chudakova’s lectures. In full, the lectures in Russian can be found here (thanks, “Arzamas”!)

Before each session, participants receive a workbook, which includes excerpts from the novel prepared for a role-play reading, quotes from literary critical works and commentaries.

Session Two, chapters 3-4

First, we turned to one of those ironical dialogues reminding the readers of the shortages experienced at the time of socialist planning and distribution: many things are just not there… it starts with the kiosk with the name “Drinks” , which only offers warm apricot water.

‘And there’s no devil either?’ the sick man suddenly inquired merrily of Ivan Nikolaevich. ‘No devil…’

‘Don’t contradict him,’ Berlioz whispered with his lips only, dropping behind the professor’s back and making faces.

‘There isn’t any devil!’ Ivan Nikolaevich, at a loss from all this balderdash, cried out not what he ought. ‘What a punishment! Stop playing the psycho!’

Here the insane man burst into such laughter that a sparrow flew out of the linden over the seated men’s heads. ‘Well, now that is positively interesting!’ the professor said, shaking with laughter.‘What is it with you – no matter what one asks for, there isn’t any!’ He suddenly stopped laughing and, quite understandably for a mentally ill person, fell into the opposite extreme after laughing, became vexed and cried sternly: ‘So you mean there just simply isn’t any?’

‘Calm down, calm down, calm down, Professor,’ Berlioz muttered, for fear of agitating the sick man. ‘You sit here for a little minute with comrade Homeless, and I’ll just run to the corner to make a phone call, and then we’ll take you wherever you like. You don’t know the city…’

In the end of the third chapter, the tone is changing. Alexander Mirer notes (in “The Ethics of Mikhail Bulgakov”): “ In the first chapter Bulgakov plays a tiny interlude comparing Mephistopheles and Woland: “Are you German? – Ivan asked. – Me? – The professor asked back and suddenly thought for a moment. – Yes, perhaps, I am a German…” The question about nationality is posed to Satan, and from Satan’s point of view it is a comical question. How can one think of asking the Prince of All Darkness such a question? So he asks back, surprised: “Me?” As if saying: I am the reason, sort of, why you people hide behind your nations, like in caves, and wait for evil caused by “enemies” or “invaders”… Then he suddenly stops and thinks. What is he thinking? Why “a liar and the father of lies” (John 8:44) does not give a quick answer, a first fiction that comes up? Well, he is not a canonical Satan, he does not put himself down by lying. On the other hand, he is not Mephistopheles either, he does not mind being recognised. He escapes into the literary spaces surrounding “The Master and Margarita”, weighs everything and returns with an answer, which vague, even strange, but quite honest in the context of the novel: “I guess, a German”… From the structure of the phrase you can already see that it is a thoughtful answer. The novel is written on the skeletal basis of the great German tragedy, as the epigraph indicates. A tragedy written by a German about a German… <…>

At the end of chapter 3, Woland’s image departs from that of Faust, and thus it will continue till the end of the novel. The death of Berlioz changes the action pace, the tone, everything. The reader, who was perhaps smiling or smirking reading about Berlioz running to make a call to the NKVD <secret police> – suddenly sees the severed head rolling on the cobblestones and the “glowing moon” shining on it. The terrifying authenticity of the event suddenly catches up with us.” End of quote.

Moving on, the group read the scene where Ivan shouts at «the professor» and his strange friend. We then followed Ivan as he ran towards Prechistenka street. It was impossible not to laugh reading about the black cat trying to buy a ticket and get on the trolleybus. Together with Ivan, we popped into a communal apartment and unwillingly saw a strange bathroom, and a communal kitchen with many primuses, one for each of many families living there.

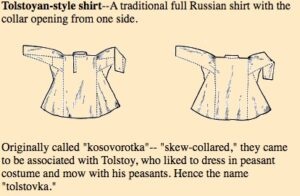

The space gets remarkably stretched, deformed in this chapter: Ivan runs as fast as he can but Woland and his retinue move away in gigantic strides. Bulgakov lets his readers witness the rite of baptism. Ivan takes his swim in the “oil-smelling water” at the foot of what had been the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour (destroyed in 1931). Then he puts a light shirt on, and gets ready to walk with a candle, to herald the coming of the evil. (Here, the participants got amused by the transformation of the word “tolstovka” as applied to clothing items – today, this is what “hoody” is called in Russian, but hundred years ago the name was applied to a Russian-style men’s shirt Leo Tolstoy used to wear.)

Ivan approaches the writers’ restaurant; he wears nothing but the tolstovka and underwear but the guard at the entrance lets him in, because Ivan shows the writers’ association membership document. Here, those groups participants representing “the parents” generation told «the children» about the utmost importance of paper documents in the USSR, and then, deviating from the subject, about registration stamps in passports and about the serfs of the twentieth century – workers of the Soviet collective farms. Our British colleague could hardly believe it, and «the children» also looked surprised although they must have heard these things before.

Session Three, Chapters 5-6

First, we discussed chapter five: Ivan comes to see his colleague writers, most of them are busy eating, drinking, dancing… while a group of twelve (a reminder of the Last Supper?) is waiting for Mikhail Berlioz, in an upper room, having no idea of the terrible accident that took place just hours ago and just a couple of hundred metres away.

The author describes a festive atmosphere and tables with food, and suddenly the action shifts to a table in a morgue, with Berlioz dead body on it… Then the grim news reaches the restaurant, the cheer dies down. However, soon enough the writers are back to their snacks and drinks. “And the ice is melting in the bowl, and at the next table you see someone’s bloodshot, bovine eyes, and you are afraid, afraid… Oh gods, my gods, poison, bring me poison!..”

The comic and the tragic are mixed even in the name of the restaurant, Griboyedov. It means “a mushroom eater”, it is at the same time a real family name of a talented nineteenth century writer who died – was killed by an outraged crowd, in fact – in Teheran where he was at diplomatic services, in his early 30s. Bulgakov adored his satirical comedy “Foe From Wit” written in 1824, staged with cuts in 1833, in full – in 1861. The main character, Chatsky, speaks uncomfortable truth, therefore “the world” thinks he is a madman. Just as they think about Jeshua in the second chapter of the novel, and about Ivan Homeless in the fifth chapter.

The participants role-played a long conversation between Ivan and a doctor in the psychiatric clinic, with some inner speech of Rühin, Ivan’s colleague, interfering in it. Rühin is another character in whom the tragic and the comic got mixed.

From the theme “the role of the writer, the role of literature” the group proceeded to the theme of Moscow. Moscow realities appear tangible and recognisable. Judging by the description of the way to the clinic, this clinic is in the north of Moscow, near Moscow river and a big parking area. On his way back Rühin is tortured by the words Ivan threw at him. “Glory will never come to someone who writes bad poems. What makes them bad? The truth, he was telling the truth! Rühin addressed himself mercilessly. ‘I don’t believe in anything I write!’”

At the last turn of the car, just before coming back to the restaurant in the House of Writers, the hopeless Rühin starts talking to the monument to Pushkin, the number one name in Russian literature. Rühin pathetically confuses facts but the readers are, again, reminded of Pushkin’s early death and, probably, of many other premature and tragic deaths of artists.

So much for the association game. In the end of the session we read aloud, in Russian and in English, the ending of the sixth chapter, which draws a trivial but amusing picture:

“A quarter of an hour later, Rükhin sat in complete solitude, hunched over his bream, drinking glass after glass, understanding and recognising that it was no longer possible to set anything right in his life, that it was only possible to forget. The poet had wasted his night while others were feasting and now understood that it was impossible to get it back. One needed only to raise one’s head from the lamp to the sky to understand that the night was irretrievably lost. Waiters were hurriedly tearing the tablecloths from the tables. The cats slinking around the veranda had a morning look. Day irresistibly heaved itself upon the poet.”

Session Four, chapters 7-8: «A Naughty Apartment » и «The Combat Between The Professor and The Poet»

The group began by role-playing the first dialogue from chapter 7, between Woland and Stepan Likhodeyev, Variety theatre director, who suffers from too much drinking the day before. The English version of a hangover remedy, “the hair of the dog”, and explanations given by British participants, aroused keen interest. Woland’s companions behave like magic folk entering the naughty apartment number fifty through a mirror in the corridor. Checking different translations of the descriptions of these appearances made us all laugh.

“And here occurred the fourth and last appearance in the apartment, as Styopa, having slid all the way to the floor, clawed at the doorpost with an enfeebled hand.” Compare: “Then occurred the fourth and last phenomenon at which Stepa collapsed entirely, his weakened hand scraping down the doorpost as he slid to the floor.”

The performance in the apartment was fun, except for internal speech of the character rendering his “most disagreeable little thoughts” at the sight of the sealed doors. When Likhodeyev looks at the seals on the doors of Berlioz rooms, he desperately tries to remember some “dubious conversations on unnecessary topics” for which he himself could be arrested.

In the eighth chapter, «The Combat Between The Professor and The Poet», calm and civilised human beings at last enter the pages of the novel – medical doctors, psychiatrists. The group looked at the description of the clinic in search for an answer to the childlike question – “is this a good place or a bad place? ” This is open to interpretation. Medicine was Mikhail Bulgakov’s first profession. Can one stop thinking like a doctor when one becomes a writer?

There was a long dialogue between Ivan and Doctor Stravinskii (another Bulgakov’s smile, reference to music) to role play and Ivan’s remarks, inner speech, to enjoy: The chief apparently made it a rule to agree with and rejoice over everything said to him by those around him, and to express this with the words ‘Very nice, very nice…’ ‘He’s intelligent,’ thought Ivan. ‘You’ve got to admit, even among intellectuals you come across some of rare intelligence, there’s no denying it.’

“Beyond the window grille, in the noonday sun, the joyful and spring-time pine wood stood beautiful on the other bank and, closer by, the river sparkled.” Those closing lines of the chapter reminded me of a song performed by a rock and roll band in the 90s, about emerald green hills and a sparkling, scintillating river in a certain fairytale country, the best in the world. “You will understand me – one cannot find a better country!” A beautiful and tearing female voice sang this to accompany one of the final scenes of “Assa”, a Soviet film that achieved cult classic status probably thanks to rock music that sounds there. Young fragile heroine has shot her mafioso boyfriend, made a call to police, and is getting dressed to head to the place of her detention.

There is a Russian saying: “Do not take it for granted that you are not in prison or not with a begging bag”. A bit too somber in translation, it sounds quite matter-of-fact in original, as just a reminder, a piece of advice.

Session Five. Chapters 9, 10, 11

Koroviev’s Stunts. News from Yalta. Ivan Splits in Two. The online meeting started with a glimpse into the “housing topic”. The participants compared original expressions with their English translations: claims to the deceased’s living space// references to unbearable overcrowding// threats, libels, denunciations// housing association// a property manager// temporary residence registration. Translated into English, the expressions lose much of their Soviet bureaucratic flavour.

Here is some historical background. Shortly after the socialist revolution, Soviet authorities developed a plan to arrange communal apartments and re-distribute square metres of those who had “too much”. Private ownership of housing was abolished in 1918, following the events of October 1917. New Soviet laws mandated the creation of public housing tenant associations. Many law-abiding but barely educated people became chairmen of such associations and were given authority to register tenants, or cancel registration – in case the person was absent for a long time. (Some of my friends have family stories about their relatives returning from the fronts of the Great Patriotic War (World War II) or from places of evacuation and finding their flats, or rooms, occupied. They had to prove their rights.)

In later Soviet times, there existed a way to invest in housing construction and get a “cooperative” flat. However, the majority of people expected the state to provide the housing; there were waiting lists. Deals masked as just exchanges were common – Koroviev, chatting with Margarita before the Ball, mentions expansion of space mastered by an entrepreneurial citizens. Since the 1990s, it became possible to establish private ownership, buy and sell properties.

Scandalous things started to happen in the recent years (2017) under the pretext of housing renovation. As compared to other alarming news, the amendments to the laws united by the word ‘renovation’ are lost; their ominous meaning is revealed only to those living in brick six-storey apartment buildings in the areas where developers can build tall towers and sell a lot more apartments. The decision on the new construction should be confirmed by local authorities, and the developers probably know how to get them interested…

– and that brings us back to Bulgakov’s text, to the scene of bribing and the remarkable expressions: thick, crackling wad// blushed deeply// It’s severely punishable //some little needle kept pricking the chairman in the very bottom of his soul…the needle of anxiety//to spit on it and not torment himself with intricate questions… // what kind of money is that? Ask five, he’ll pay it// “cash loves counting”, “your own eye won’t lie”.

There was an interesting moment when the group read what Koroviev was saying on the phone pretending to be a neighbour reporting manager Bosoi as someone who hides foreign currency. First, the focus was on a peculiar style of speaking, a Soviet bureaucratic language mixed with colloquial words. Then, our British participant admitted that he found the idea of reporting someone to the authorities sound “very foreign”. The Russian part of the group remembered Prince Hamlet’s childhood friends who betrayed him yet, true, it was not medieval Denmark we were talking about, but 1930s. It was impossible not to remember Sergei Dovladov’s “We endlessly criticise Comrade Stalin, and, of course, for the cause. Still, I want to ask – who has written four million denunciations?”

We then proceeded to the picturesque episode “Dollars in the ventilation… your little wad?’ – ‘No! Enemies stuck me with it!’ – ‘That happens,’ the first agreed and added, again gently: ‘Well, you are going to have to turn in the rest.” Everyone laughed, but the ominous theme of denunciations, disappearance of the accused and then of the informers was hovering around.

Chapter ten is packed with details and references to the musical world. To keep the thread of events, we focused on reading telegrams and threatening warnings received by the Variety Theatre administrator on the phone and in person. The fantastic staff got condensed and then erupted in a thunderstorm and heavy rain over Moscow.

In the noise of the thunderstorm the administrator, Varenukha, in shock after punches and threats, was kissed by Gella-the-vampire while the readers are taken by the storm from the Garden Ring to the clinic where Ivan Homeless is being treated. After Ivan’s conversation with his alter ego, in the last lines of Chapter 11, Bulgakov makes Ivan’s neighbour to appear. No mistake to be made, the readers are going to meet one of the main protagonists – at last! Finally, we are going to talk about love of the Master and Margarita.

Sixth session, chapters 12-15

During this session, we focused on a number of fascinating excerpts from the novel’s text: a Variety Theatre performance with elements of black magic; a frantic escape of suddenly old and gray-haired Mr.Rimsky, a showcase interrogation in Mr.Bosoi’s dream. It is time for one of the Woland’s most famous quotes: “Well, now, they’re people like any other people… They love money, but that has always been so… Mankind loves money, whatever it’s made of – leather, paper, bronze, gold. Well, they’re light-minded…well, what of it… mercy sometimes knocks at their hearts… ordinary people… In general, reminiscent of the former ones… only the housing problem has corrupted them…’And he ordered loudly: ‘Put the head on.”

“The séance is over! Maestro! Hack out a march! The half-crazed conductor, unaware of what he was doing, waved his baton, and the orchestra did not play, or even strike up, or even bang away at, but precisely, in the cat’s loathsome expression, hacked out some incredible march of an unheard-of brashness.”

“… people were climbing over the barriers, there were bursts of infernal guffawing and furious shouts, drowned in the golden clash of the orchestra’s cymbals.»

The next, thirteenth, chapter, about Master, contrasts with the bizarre circus scenes and café-chantant music. There are parallels between Master and Ivan Homeless as well as between Master and Bulgakov. Both Ivan and Master are interested in the story told in the gospels and ended up in the psychiatrist’s clinic “because of the Pontius Pilate”. Both Master and Bulgakov are historians and writers. Master writes a novel about Pilate, and just as Bulgakov’s book we are reading, his novel ends with the words “…the cruel fifth procurator of Judea, the equestrian Pontius Pilate.” The echo of the painful dramas is heard throughout this part of the book. Intrigues in the world or writers’ and critics caused Master’s illness. He could not imagine himself without writing, but editors would not publish his novel. Margarita and Master were happy together but it did not last long. She was going to talk to her husband and then move in, to stay and live with Master, but this did not come to pass.

Here is a quote from lectures of Marietta Chudakova, a Russian scholar who spent years studying Bulgakov’s archives and talked a lot with his widow, Elena Sergeyevna Bulgakova: “The novel is full of everyday details of life as it was then. If you were someone like Bulgakov informers were waiting at every corner. It does sound odd but at some point the Russian Federal Security Service published, in photocopies and in a very small circulation, the informants’ reports. Reading them makes one ask: did Bulgakov spend at least an hour of his life without the informants? One of them, as Elena Sergeyevna told me herself, was the prototype of Aloysius Mogarych in the novel. It was Emmanuel Zhukhovitsky who worked as interpreter and translator. Bulgakov saw through him instantly. Zhukhovitski often visited them and hurried to Lubyanka in the evenings: reports had to be written in the state security office at Lubianka on the same day.” <Later, Zhukhovitsky himself was arrested and perished – NW>

“I want to warn everyone that you cannot accuse people who became informers in those years, because they were all too often under the threat of being shot. <…> We need to clearly distinguish between the time of the Big Terror and the 1960s and 1970s. In those years, in the 60’s and 70’s, they <KGB> tried to recruit everyone. We always despised those who agreed to this. Because they didn’t face a bullet, and everything else could be tolerated. “<…>

Margarita writes to her husband when she is about to fly away: “I have turned into a witch from the grief and distress that had afflicted me”. Why she mixes with “unclean power”? For anyone, and especially for the son of a professor at the Theological Academy (Bulgakov’s father was lecturing in Kiiv academy), things were quite straightforward. One must not associate with dark forces! Finally, I got it figured out. They used to visit the American embassy, they invited guests over to their place. At such meetings, there was bound to be an informer. Sometimes there was Zhukhovitsky, sometimes someone else, and sometimes nobody! How did the NKVD receive information? There are not so many answers to this question.

I wondered why someone who understands perfectly well what a witch is in Russian consciousness and Russian folklore would call a novel “The Master and Margarita”. The first part of the title is a direct reference to the author and his hero, the author’s alter ego. “…and Margarita.” So Margarita must be a close friend of the author’s alter ego. Elena Sergeevna has always emphasised that she had been the prototype of Margarita and that Bulgakov had meant it that way. “What a monument I’ve raised to you!” – he once said to her.

So why he made a witch out of his beloved one? Here is the conclusion I came to, and I am fully responsible for it. He learned – from her, or in some other way – that she, as a result of some circumstances, had fallen into the clutches of these people, and he agonised trying to reconcile with himself. Most writers do not just describe to us some things that surround them – they solve some internal problem they have. Pushkin and Lermontov have a lot of that – as well as Bulgakov. He was solving his inner problem. And he gave us the answer. He solved it in “The Master and Margarita”. Yes, she is in contact with evil forces, which is a very controversial thing to us Russians. But she does it for his sake, to save him. The novel states it directly and clearly. Bulgakov resolves the doubts and takes the burden of guilt off her.

You can read “The Master and Margarita” perfectly well without knowing or thinking about these things. However, if we want to associate it in some way with Bulgakov’s biography, this is the interpretation I propose, and it reflects the incredible tragedy of that time. Those who argue that the comments cast shadow on Bulgakov himself, they just do not understand the lives of people who went to bed at night, not knowing whether they would wake up in their own bed or in a torture chamber at the Lubyanka. And how people lived, I still cannot imagine.” End of quote.

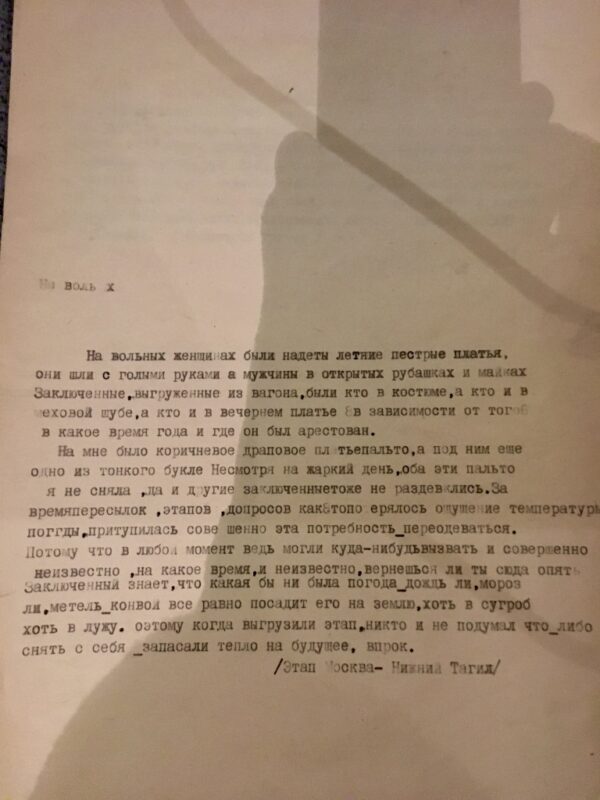

The first document is not signed, it looks like a diary or a memory. Here is what it says:

“…The free women wore brightly coloured summer dresses and walked bare-armed, while the men wore open shirts and T-shirts. The prisoners unloaded from the wagon wore suits, or fur coats, or even evening gowns, depending on when and where they were arrested. I was wearing a brown drape dress-coat, and another one, of fine bouclé, underneath. Despite the heat of the day, I did not take off both coats, and neither did the other prisoners. In the course of the prisoners’ transportations and interrogations, I somehow lost my sense of temperature and weather, and the need to change clothes became completely dulled. Because at any moment you could be summoned somewhere, and you don’t know for how long, and you don’t know if you will come back here again. Prisoners know that whatever the weather – rain, frost, blizzard – the convoy will put them on the ground, whether in a snowdrift or in a puddle. So when they unloaded us at a station, nobody thought to take anything off – we were saving warmth for the future. (Moscow – Nizhniy Tagil prisoners transportation staging post)”

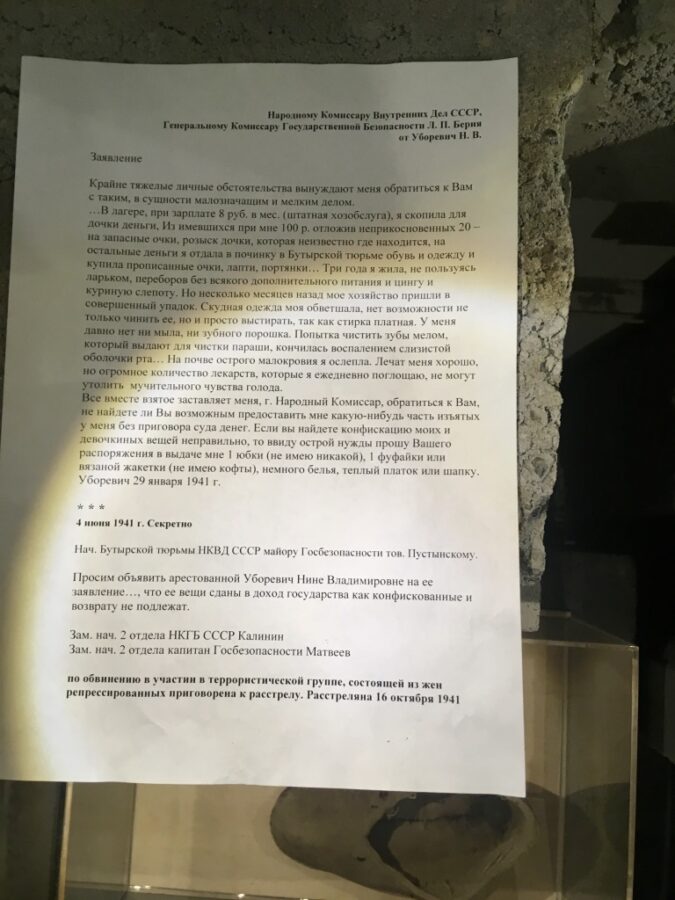

The second document ends with a comment about the execution of the author, Nina Uborevich in October 1941. Her husband Ieronim Uborevich, a Soviet military commander, was executed earlier, in June 1937; both were posthumously rehabilitated in the 1950s. Their daughter Mira (Vladimira, parents named her after Vladimir Lenin) left memoirs, in the form of letters to Elena Sergeevna Bulgakova whom she knew and loved. Elena’s first husband whom she left to marry Mikhail Bulgakov, was also a top-ranking military specialist, they and Uborevich family were neighbours. Mira Uborevich’s text, “Fourteen Letters to Elena Sergeyevna Bulgakova. A documentary novel”, in Russian, can be found here

Here is the text of Nina Uborevich’s request and then KGB verdict:

People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR General Commissar of State Security L.P.Beria From Uborevich N. V. Statement Extremely grave personal circumstances compel me to address you with such an essentially insignificant and minor matter. …In the camp, with a salary of 8 roubles per month (as one of maintenance staff) I had saved up money for my daughter. Out of the 100 roubles which I had, I put aside 20 roubles for spare glasses and to search for my daughter, as I do not know where she is, and with the rest of the money I repaired shoes and clothing at Butyrskaya prison shop, and bought prescribed glasses, straw shoes and footwraps… I lived three years without buying things in the prison’s kiosk, and I got over scurvey disease and hemeralopia without any additional food. But a few months ago my things became completely non-repairable. My meagre clothes are dilapidated, there is no way to not only mend them, but to simply wash them, as there is a charge for laundry. I haven’t had soap or toothpaste for a long time. I have tried to brush my teeth with chalk given out to clean gut buckets and ended up with an inflammation of the mucous membrane of my mouth… I have gone blind because of acute anaemia. They are treating me well but the huge amount of medicine I consume on a daily basis cannot satisfy my appetite. All of this makes me, Mr. People’s Commissar, to ask you if you would find it possible to give me some of the money that has been confiscated from me without a court verdict. If you find the confiscation of my and my girl’s belongings improper, in view of the dire need, I ask for your instruction that I be given one skirt (I do not have any), one padded or knitted jacket (I have none), some underwear, a warm scarf or a warm cap. Signed: Uborevich, 29 January 1941. *** June 4, 1941. Secret. Head of Butyrskaya Penitentiary Prison, USSR NKVD, Major of State Security, Comrade Pustynsky. We ask to inform the arrested Nina Vladimirovna Uborevich, on her statement … that her belongings have been considered the state’s income as confiscated property and cannot be returned. Deputy Chief of the 2nd Division of the USSR NKGB Kalinin Deputy Chief of 2nd Division, Captain Matveev Sentenced to death on charges of taking part in a terrorist group consisting of the wives of the repressed. Shot on the 16th of October, 1941.

Back to the novel. At the end of the session we read excerpts from Chapter 15 about the escape of the Variety Theatre finance director Mr. Rimsky, who had experienced meeting the “unclean powers”, and about the dream of the housing manager Mr.Bosoi, how he was interrogated in the arena of the circus. Funny, but so scary, “oh gods, gods…”

Here is some three quotes:

1) ‘Make the Leningrad express, I’ll tip you well,’ the old man said, breathing heavily and clutching his heart. ‘I’m going to the garage,’ the driver answered hatefully and turned away. Then Rimsky unlatched his briefcase, took out fifty roubles, and handed them to the driver through the open front window. A few moments later, the rattling car was flying like the wind down Sadovoye Ring. The passenger was tossed about on his seat, and in the fragment of mirror hanging in front of the driver, Rimsky saw now the driver’s happy eyes, now his own insane ones.”

2) “’As God is true, as God is almighty,’ Nikanor Ivanovich began, ‘he sees everything, and it serves me right. I never laid a finger on it, never even suspected what it was, this currency! God is punishing me for my iniquity.’ Nikanor Ivanovich went on with feeling, now buttoning, now unbuttoning his shirt, now crossing himself. ‘I took! I took, but I took ours. Soviet money! I’d register people for money, I don’t argue, it happened. Our secretary Bedsornev is a good one, too, another good one! Frankly speaking, there’s nothing but thieves in the house management… But I never took currency!’

3) “Before his dream, Nikanor Ivanovich had been completely ignorant of the poet Pushkin’s works, but the man himself he knew perfectly well and several times a day used to say phrases like: ‘And who’s going to pay the rent – Pushkin?’ or ‘Then who did unscrew the bulb on the stairway – Pushkin?’ or ‘So who’s going to buy the fuel – Pushkin?’

Session Seven. Yershalaim Chapters: 2, 16, 25, 26

The line of Pontius Pilate and Yeshua sounds in counterpoint to the other chapters in the novel. The tone of the four chapters, set in Yershalaim, is serious and realistic, no irony, no fairy tale flavour, no grotesque, no absurd moments. On the surface, the story resembles an interpretation of the events registered in the Gospels, but from the very beginning Bulgakov emphasises that Yeshua is not Christ.

Yeshua does not remember his parents, he has only one disciple, he believes that all people are good and kind, he entered the city on foot, not on a donkey, in silence, not to the cheers of the crowd… He is a wandering philosopher, perhaps a healer, but not a messiah. After his death on the cross, Yeshua’s body is taken by a disciple, not by a rich righteous man, as the evangelists have it. Judas, who betrayed Christ, kills himself. In Bulgakov’s story, Judas is killed by Pilate who had been tormented by a feeling of guilt.

Why does Bulgakov tell the well-known story differently, what is his message? We turned to a detailed analysis done by Alexander Mirer in his book “Mikhail Bulgakov’s Gospel”. Here is an excerpt: “The slogan ‘love your enemies’ served as a battering ram, after which some essential and tangible rules of fellowship penetrated the European morality… <…> These days no reasonable person questions the value of the Sermon on the Mount. But it seems that Jesus himself understood his sermon not as we do, and had a different social benefit in mind. He proclaimed moral perfection as a prerequisite for the salvation of his adherents from God’s punishment at the Last Judgment. But Bulgakov knew all this too, and probably realised that the Gospel account of the Roman procurator’s attempts to save Christ was not just far from the truth, but was perhaps the weakest point of the whole Gospel story. And yet he built his account around Pilate’s intercession and then Pilate’s apostasy.

Why? The first answer is, it is the nature of the profession. Literature begins where an elementary logic of behaviour breaks down. The second answer is that every writer is attracted by conflicts between the individual and the pressures of the social system. The story of Pontius Pilate is the conflict between conscience and social duty – in the popular form, which is the commonplace within the Christian tradition: a certain Roman judge commits an act of betrayal <…> Under the pressure of socially significant forces, he betrays his conscience and sends a human being to die.” End of quote

We read Pilate’s dialogues with the chief of the secret police and saw these themes unfolding: power, authority, state institutions, the curse of the system. All the agnostics of the group now know that “where they will remember me, they will remember you” is a reference to a prayer that Christians recite at every liturgy, the “Symbol of Faith.” The prayer dates back to the fourth century AD; surprisingly, Bulgakov’s Yeshua is aware of the text.

Session Eight. Chapters 22-24: «By Candlelight», «The Great Ball of Satan’s», «The Extraction of the Master»

The workbook I made for this chapter included a lot of comments – about a book called “The History of Man’s Intercourse with the Devil” and “black masses”, famous chess matches, Avadonna from the Apocalypse and the war in Spain, covered daily by radio in May 1937 (annoying Woland, as he put it), about the villains and the executioners who flashed at the ball. The comments were for participants to read in advance, as the whole time of the session was devoted to the splendid dialogues chapters 22-24 have to offer.

Nine of those we played during the session enjoying every minute of it. It was one of the participants who drew everyone’s attention to the way the cat’s name was rendered in the English text – not Hippopotamus but Behemoth, the name for a mythological, biblical, demon.

Session Nine

We read several marvellous scenes and dialogues to reflect on the statement “According to your faith be it done to you.” “Master and Margarita” is a great and inexhaustible book. The group decided to continue sessions and to start to read Nikolai Gogol. This way, we will also continue talking about Mikhail Bulgakov who considered himself Gogol’s apprentice.